An atom with no valence electrons B. An atom with one valence electron C. An atom with two valence electrons D. An atom with three valence electrons I think it is B. Arrange the elements in decreasing order of the number of valence electrons Br,S,Sb,Sr,F,Mg,I,Ca,Na,Kr,Xe,Bi,Ge,Ga,K. Valence is an older term that describes how many other atoms an atom can bond with. Valence electrons are the number of outer shell electrons an atom has.

Apr 20, 2021 Now, for the oxygen atom, its atomic number is eight whereas the electronic configuration is 1s2 2s2 2p4. As p shell can allow six electrons, there is a scarcity of only two electrons. Due to this, the maximum valence electrons in a single oxygen atom is six.

Ionic Bonding

Soduim atom'>We have learned that atoms tend to react in ways that create a full valence shell, but what does this mean? Sodium (Na), for example, has one electron in its valence shell. This is an unstable state because that valence shell needs eight electrons to be full. In order to fill its valence shell, sodium has two options:

Helium

- Find a way to add seven electrons to its valence shell, or

- Give up that one electron so the next lower energy shell (already full) could become its new valence shell.

Which do you think is more easily accomplished?

Right, giving up one electron! Atoms like sodium, with only one or two electrons in a valence shell that needs eight electrons, are most likely to give up their valence electrons to achieve a stable state. All these atoms need is another atom that can attract their electrons!

An atom such as chlorine (Cl), that contains seven electrons in its valence shell, needs one more electron to have a full valence shell. If we use the same logic as we did for sodium, we should conclude that chlorine would rather gain one more electron than lose all seven of its valence electrons to achieve stability. Under the right conditions, atoms like chlorine will steal an electron from nearby atoms like sodium. This ability to pull electrons away from other atoms is termed electronegativity. Atoms with a valence shell that is almost full are more likely to be electronegative because they have greater reason to pull electrons towards them. Electronegative atoms are not negatively charged, but they are more likely to become negatively charged.

When an electron moves from one atom to another, both atoms become ions. An ion is any atom that has gained electrons to have a negative charge (anion) or lost electrons to have a positive charge (cation). An easy way to remember that a cation has a positive, or +, charge is to think of the letter t in the word cation as a + sign.

Once an atom becomes an ion, it has an electrical charge. Ions of opposite charge are attracted to one another, forming a chemical bond, an association formed by attraction between two atoms. This type of chemical bond is called an ionic bond because the bond formed between two ions of opposite charge. The sodium cation (Na+) and the chlorine anion (Cl-) are attracted to one another to form sodium chloride, or table salt.

Although ionic bonds are very strong, they can be relatively easily broken if another attractive ion (or polar molecule) comes around. An ionic bond is formed when two ions of opposite charge come together by attraction, NOT when an electron is transferred.

Think of ionic bond formation as the second step in a two step process:

- Two atoms each become ions. The atoms could have become ions in previous reactions with other atoms or the atoms may have reacted with each other, transferring the electron(s) from one to the other.

- The two ions of opposite charge “see” one another and become attracted enough to form the bond.

Ionic Bonding

This video visually illustrates how atoms form ionic bonds.

Create an Ionic Bond

In this activity, you'll create cations and anions and watch the ionic bond form.

Covalent Bonding

Carbon atom'>In ionic bonding, we looked at atoms with either one or two electrons in their valence shell and atoms that only needed one or two electrons to fill their valence shell. What happens when an atom, carbon (C) for example, has four valence electrons? Carbon would need to either lose four electrons or gain four electrons in order to have a full valence shell. Both of these situations would cause carbon to have a very strong charge, which would probably make it as unstable as having an incomplete valence shell! For atoms like carbon, there is another option: sharing.

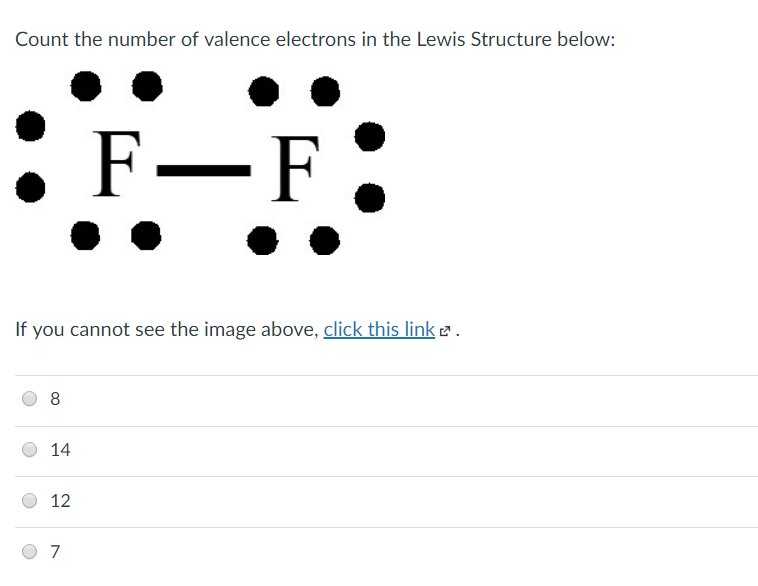

When two atoms each need additional electrons to fill their valence shells, but neither is electronegative enough to steal electrons from the other, they can form another kind of chemical bond called a covalent bond. In covalent bonds, two atoms move close enough to share some electrons. The electrons from each atom shift to spend time moving around both atomic nuclei.

In the most common form of covalent bond, a single covalent bond, two electrons are shared, one from each atom’s valence shell. Double covalent bonds where four electrons are shared, and triple covalent bonds where six electrons are shared, are also commonly found in nature.

How do we know if and when covalent bonds will form? Atoms will form as many covalent bonds as it takes to fill their valence shell. This means that carbon, our previous example, will need to form four covalent bonds in order to fill its outermost shell. In each of the four bonds, carbon will contribute one electron and the other atom will contribute one electron, supplying carbon with eight electrons effectively orbiting its nucleus. Atoms like oxygen (O) will form two covalent bonds because they already have six valence electrons and only need two more electrons obtained by sharing. Put another way, oxygen shares two of its six valence electrons in covalent bonds while keeping four valence electrons for itself (4 unshared oxygen electrons + 2 shared oxygen electrons + 2 shared electrons from the other atoms = 8 total electrons).

In shell models, the shared electrons are shown within the overlapping region of the valence shells to represent the fact they are shared, but the electrons are actually moving around both nuclei and could be found anywhere around either nucleus at a given time.

For simplicity, we often draw covalent bonds as straight lines between atoms to represent the structural formula. Each line represents a single covalent bond (two shared electrons), so double lines represent a double covalent bond (four shared electrons).

Covalent bonds are usually found in atoms that have at least two, and usually less than seven, electrons in their outermost energy shell, but this is NOT a hard and fast rule. Hydrogen, for example, is a unique atom that bears closer examination. Because hydrogen only has one electron surrounding its nucleus, its valence shell is the first energy shell, which only needs two electrons to be full. Hydrogen tends to form covalent bonds because a single covalent bond will fill its shell. However, the one-proton nucleus is very weak and has trouble keeping the shared electrons around the hydrogen atom for very long.

Covalent Bonding

This video visually illustrates how atoms form covalent bonds.

Other Kinds of Bonding

When a covalent bond forms between atoms of similar electronegativity, the shared electrons tend to spend equal time around each nucleus. What happens if a bond is formed between atoms like oxygen, which is highly electronegative, and hydrogen, which is not? The oxygen atom tends to pull the shared electrons over to its side of the bond more often than the hydrogen atom does, resulting in polarity, or a partial separation of charge between atoms. The electrons don’t actually leave the less electronegative atom, but they do spend less time on that side. This results in two poles, one slightly positive and one slightly negative. This is called a polar bond, while covalent bonds where electrons are shared equally are called nonpolar.

Polar covalent bonds are the source of an additional kind of association called a hydrogen bond. In a hydrogen bond, the partially positive end of a polar covalent molecule is attracted to the partially negative end of another polar covalent molecule. For example, water is composed of two hydrogen atoms covalently bonded to a single oxygen atom. In a container full of water molecules, the hydrogen atoms of each water molecule are attracted to the oxygen atoms of other water molecules, forming hydrogen bonds between all of the molecules in the container of water. Hydrogen bonds are weak compared to covalent bonds, but they are strong enough to affect the behavior of the atoms involved. This leads to many important chemical properties in water and other molecules.

Skills to Develop

- To understand three ways that molecules and ions violate the Octet Rule

Three cases can be constructed that do not follow the octet rule, and as such, they are known as the exceptions to the octet rule. Following the Octet Rule for Lewis Dot Structures leads to the most accurate depictions of stable molecular and atomic structures and because of this we always want to use the octet rule when drawing Lewis Dot Structures. However, it is hard to imagine that one rule could be followed by all molecules. There is always an exception, and in this case, three exceptions:

- When there are an odd number of valence electrons

- When there are too few valence electrons

- When there are too many valence electrons

Exception 1: Species with Odd Numbers of Electrons

The first exception to the Octet Rule is when there are an odd number of valence electrons. An example of this would be Nitrogen (II) Oxide (NO ,refer to figure one). Nitrogen has 5 valence electrons while Oxygen has 6. The total would be 11 valence electrons to be used. The Octet Rule for this molecule is fulfilled in the above example, however that is with 10 valence electrons. The last one does not know where to go. The lone electron is called an unpaired electron. But where should the unpaired electron go? The unpaired electron is usually placed in the Lewis Dot Structure so that each element in the structure will have the lowestformal charge possible. The formal charge is the perceived charge on an individual atom in a molecule when atoms do not contribute equal numbers of electrons to the bonds they participate in.

No formal charge at all is the most ideal situation. An example of a stable molecule with an odd number of valence electrons would be nitrogen monoxide. Nitrogen monoxide has 11 valence electrons. If you need more information about formal charges, see Lewis Structures. If we were to imagine nitrogen monoxide had ten valence electrons we would come up with the Lewis Structure (Figure 3.8.1):

Figure 3.8.1: This is if nitrogen monoxide has only ten valence electrons, which it does not.

Let's look at the formal charges of Figure 3.8.2 based on this Lewis structure. Nitrogen normally has five valence electrons. In Figure 3.8.1, it has two lone pair electrons and it participates in two bonds (a double bond) with oxygen. This results in nitrogen having a formal charge of +1. Oxygen normally has six valence electrons. In Figure 3.8.1, oxygen has four lone pair electrons and it participates in two bonds with nitrogen. Oxygen therefore has a formal charge of 0. The overall molecule here has a formal charge of +1 (+1 for nitrogen, 0 for oxygen. +1 + 0 = +1). However, if we add the eleventh electron to nitrogen (because we want the molecule to have the lowest total formal charge), it will bring both the nitrogen and the molecule's overall charges to zero, the most ideal formal charge situation. That is exactly what is done to get the correct Lewis structure for nitrogen monoxide (Figure 3.8.2):

Figure 3.8.2: The proper Lewis structure for NO molecule

Free Radicals

There are actually very few stable molecules with odd numbers of electrons that exist, since that unpaired electron is willing to react with other unpaired electrons. Most odd electron species are highly reactive, which we call Free Radicals. Because of their instability, free radicals bond to atoms in which they can take an electron from in order to become stable, making them very chemically reactive. Radicals are found as both reactants and products, but generally react to form more stable molecules as soon as they can. In order to emphasize the existence of the unpaired electron, radicals are denoted with a dot in front of their chemical symbol as with (cdot OH), the hydroxyl radical. An example of a radical you may by familiar with already is the gaseous chlorine atom, denoted (cdot Cl). Interestingly, odd Number of Valence Electrons will result in the molecule being paramagnetic.

Exception 2: Incomplete Octets

The second exception to the Octet Rule is when there are too few valence electrons that results in an incomplete Octet. There are even more occasions where the octet rule does not give the most correct depiction of a molecule or ion. This is also the case with incomplete octets. Species with incomplete octets are pretty rare and generally are only found in some beryllium, aluminum, and boron compounds including the boron hydrides. Let's take a look at one such hydride, BH3 (Borane).

If one was to make a Lewis structure for BH3following the basic strategies for drawing Lewis structures, one would probably come up with this structure (Figure 3.8.3):

Figure 3.8.3

The problem with this structure is that boron has an incomplete octet; it only has six electrons around it. Hydrogen atoms can naturally only have only 2 electrons in their outermost shell (their version of an octet), and as such there are no spare electrons to form a double bond with boron. One might surmise that the failure of this structure to form complete octets must mean that this bond should be ionic instead of covalent. However, boron has an electronegativity that is very similar to hydrogen, meaning there is likely very little ionic character in the hydrogen to boron bonds, and as such this Lewis structure, though it does not fulfill the octet rule, is likely the best structure possible for depicting BH3 with Lewis theory. One of the things that may account for BH3's incomplete octet is that it is commonly a transitory species, formed temporarily in reactions that involve multiple steps.

Let's take a look at another incomplete octet situation dealing with boron, BF3(Boron trifluorine). Like with BH3, the initial drawing of a Lewis structure of BF3 will form a structure where boron has only six electrons around it (Figure 3.8.4).

Figure 3.8.4

If you look Figure 3.8.4, you can see that the fluorine atoms possess extra lone pairs that they can use to make additional bonds with boron, and you might think that all you have to do is make one lone pair into a bond and the structure will be correct. If we add one double bond between boron and one of the fluorines we get the following Lewis Structure (Figure 3.8.5):

Figure 3.8.5

Each fluorine has eight electrons, and the boron atom has eight as well! Each atom has a perfect octet, right? Not so fast. We must examine the formal charges of this structure. The fluorine that shares a double bond with boron has six electrons around it (four from its two lone pairs of electrons and one each from its two bonds with boron). This is one less electron than the number of valence electrons it would have naturally (Group Seven elements have seven valence electrons), so it has a formal charge of +1. The two flourines that share single bonds with boron have seven electrons around them (six from their three lone pairs and one from their single bonds with boron). This is the same amount as the number of valence electrons they would have on their own, so they both have a formal charge of zero. Finally, boron has four electrons around it (one from each of its four bonds shared with fluorine). This is one more electron than the number of valence electrons that boron would have on its own, and as such boron has a formal charge of -1.

This structure is supported by the fact that the experimentally determined bond length of the boron to fluorine bonds in BF3 is less than what would be typical for a single bond (see Bond Order and Lengths). However, this structure contradicts one of the major rules of formal charges: Negative formal charges are supposed to be found on the more electronegative atom(s) in a bond, but in the structure depicted in Figure 3.8.5, a positive formal charge is found on fluorine, which not only is the most electronegative element in the structure, but the most electronegative element in the entire periodic table ((chi=4.0)). Boron on the other hand, with the much lower electronegativity of 2.0, has the negative formal charge in this structure. This formal charge-electronegativity disagreement makes this double-bonded structure impossible.

However the large electronegativity difference here, as opposed to in BH3, signifies significant polar bonds between boron and fluorine, which means there is a high ionic character to this molecule. This suggests the possibility of a semi-ionic structure such as seen in Figure 3.8.6:

Figure 3.8.6

None of these three structures is the 'correct' structure in this instance. The most 'correct' structure is most likely a resonance of all three structures: the one with the incomplete octet (Figure 3.8.4), the one with the double bond (Figure 3.8.5), and the one with the ionic bond (Figure 3.8.6). The most contributing structure is probably the incomplete octet structure (due to Figure 3.8.5 being basically impossible and Figure 3.8.6 not matching up with the behavior and properties of BF3). As you can see even when other possibilities exist, incomplete octets may best portray a molecular structure.

As a side note, it is important to note that BF3 frequently bonds with a F- ion in order to form BF4- rather than staying as BF3. This structure completes boron's octet and it is more common in nature. This exemplifies the fact that incomplete octets are rare, and other configurations are typically more favorable, including bonding with additional ions as in the case of BF3 .

Example 3.8.1: (NF_3)

Draw the Lewis structure for boron trifluoride (BF3).

SOLUTION

1. Add electrons (3*7) + 3 = 24

2. Draw connectivities:

3. Add octets to outer atoms:

4. Add extra electrons (24-24=0) to central atom:

5. Does central electron have octet?

- NO. It has 6 electrons

- Add a multiple bond (double bond) to see if central atom can achieve an octet:

6. The central Boron now has an octet (there would be three resonance Lewis structures)

However...

- In this structure with a double bond the fluorine atom is sharing extra electrons with the boron.

- The fluorine would have a '+' partial charge, and the boron a '-' partial charge, this is inconsistent with the electronegativities of fluorine and boron.

- Thus, the structure of BF3, with single bonds, and 6 valence electrons around the central boron is the most likely structure

BF3 reacts strongly with compounds which have an unshared pair of electrons which can be used to form a bond with the boron:

Exception 3: Expanded Valence Shells

More common than incomplete octets are expanded octets where the central atom in a Lewis structure has more than eight electrons in its valence shell. In expanded octets, the central atom can have ten electrons, or even twelve. Molecules with expanded octets involve highly electronegative terminal atoms, and a nonmetal central atom found in the third period or below, which those terminal atoms bond to. For example, (PCl_5) is a legitimate compound (whereas (NCl_5)) is not:

Note

Expanded valence shells are observed only for elements in period 3 (i.e. n=3) and beyond

The 'octet' rule is based upon available ns and np orbitals for valence electrons (2 electrons in the s orbitals, and 6 in the p orbitals). Beginning with the n=3 principle quantum number, the d orbitals become available (l=2). The orbital diagram for the valence shell of phosphorous is:

O Has How Many Valence Electrons

Hence, the third period elements occasionally exceed the octet rule by using their empty d orbitals to accommodate additional electrons. Size is also an important consideration:

- The larger the central atom, the larger the number of electrons which can surround it

- Expanded valence shells occur most often when the central atom is bonded to small electronegative atoms, such as F, Cl and O.

There is currently much scientific exploration and inquiry into the reason why expanded valence shells are found. The top area of interest is figuring out where the extra pair(s) of electrons are found. Many chemists think that there is not a very large energy difference between the 3p and 3d orbitals, and as such it is plausible for extra electrons to easily fill the 3d orbital when an expanded octet is more favorable than having a complete octet. This matter is still under hot debate, however and there is even debate as to what makes an expanded octet more favorable than a configuration that follows the octet rule.

One of the situations where expanded octet structures are treated as more favorable than Lewis structures that follow the octet rule is when the formal charges in the expanded octet structure are smaller than in a structure that adheres to the octet rule, or when there are less formal charges in the expanded octet than in the structure a structure that adheres to the octet rule.

Example 3.8.2: The (SO_4^{-2}) ion

Such is the case for the sulfate ion, SO4-2. A strict adherence to the octet rule forms the following Lewis structure:

Figure 3.8.12

If we look at the formal charges on this molecule, we can see that all of the oxygen atoms have seven electrons around them (six from the three lone pairs and one from the bond with sulfur). This is one more electron than the number of valence electrons then they would have normally, and as such each of the oxygens in this structure has a formal charge of -1. Sulfur has four electrons around it in this structure (one from each of its four bonds) which is two electrons more than the number of valence electrons it would have normally, and as such it carries a formal charge of +2.

If instead we made a structure for the sulfate ion with an expanded octet, it would look like this:

Figure 3.8.13

Looking at the formal charges for this structure, the sulfur ion has six electrons around it (one from each of its bonds). This is the same amount as the number of valence electrons it would have naturally. This leaves sulfur with a formal charge of zero. The two oxygens that have double bonds to sulfur have six electrons each around them (four from the two lone pairs and one each from the two bonds with sulfur). This is the same amount of electrons as the number of valence electrons that oxygen atoms have on their own, and as such both of these oxygen atoms have a formal charge of zero. The two oxygens with the single bonds to sulfur have seven electrons around them in this structure (six from the three lone pairs and one from the bond to sulfur). That is one electron more than the number of valence electrons that oxygen would have on its own, and as such those two oxygens carry a formal charge of -1. Remember that with formal charges, the goal is to keep the formal charges (or the difference between the formal charges of each atom) as small as possible. The number of and values of the formal charges on this structure (-1 and 0 (difference of 1) in Figure 3.8.12, as opposed to +2 and -1 (difference of 3) in Figure 3.8.12) is significantly lower than on the structure that follows the octet rule, and as such an expanded octet is plausible, and even preferred to a normal octet, in this case.

Example 3.8.3: The (ICl_4^-) Ion

Draw the Lewis structure for (ICl_4^-) ion.

SOLUTION

1. Count up the valence electrons: 7+(4*7)+1 = 36 electrons

2. Draw the connectivities:

3. Add octet of electrons to outer atoms:

4. Add extra electrons (36-32=4) to central atom:

5. The ICl4- ion thus has 12 valence electrons around the central Iodine (in the 5d orbitals)

Expanded Lewis structures are also plausible depictions of molecules when experimentally determined bond lengths suggest partial double bond characters even when single bonds would already fully fill the octet of the central atom. Despite the cases for expanded octets, as mentioned for incomplete octets, it is important to keep in mind that, in general, the octet rule applies.

Outside links

References

- Petrucci, Ralph H.; Harwood, William S.; Herring, F. G.; Madura, Jeffrey D. General Chemistry: Principles & Modern Applications. 9th Ed. New Jersey. Pearson Education, Inc. 2007.

- Moore, John W.; Stanitski, Conrad L.; Jurs, Peter C. Chemistry; The Molecular Science. 2nd Ed. 2004.

Contributors

Mike Blaber (Florida State University)